Nova Cæsarea: A Cartographic Record of the Garden State, 1666-1888

State of New Jersey: First Wall Maps and Atlases (1812–1888)

![1812: William Watson. "A Map of the State of New Jersey. To His Excellency, Joseph Bloomfield, Governor, the Council and Assembly of the State of New Jersey: This Map Is Respectfully Inscribed" (Philadelphia: W. Harrison, September 25, 1812) [Historic Maps Collection]. Wall map, with added color, 99 × 67.7 cm. Scale: 4 miles to 1 inch. One of three known institutional copies.](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fintro%2F1812-watson-state-map.jp2/full/!750,750/0/default.jpg)

First wall map of the state and the first map to show all of its townships. A number of those townships are outlined in color, as are the thirteen counties (named in large capital letters): Bergen, Burlington, Cape May, Cumberland, Essex, Gloucester, Hunterdon, Middlesex, Monmouth, Morris, Salem, Somerset, and Sussex. Occasionally, a personal residence is named, such as "Witherspoon's" between Rocky Hill and Princeton in Montgomery Township. This one refers to the home of John Witherspoon (1723–1794), a former president of the College of New Jersey (Princeton University.) At the top left, Watson has placed a large representation of the state seal, and he dedicates his map to Joseph Bloomfield, the state's fourth governor, whose term ended in 1812. Longitude is shown east and west from Philadelphia.

A period of five years separated the prospectus for the map, which had appeared in the Trenton Federalist, and its apparent completion:

Map of New-Jersey.

---

PROPOSALS,

For publishing by Subscription, a large and complete Map of the State of New-Jersey.

The Map is divided into East and West, and subdivided into Counties and Townships, agreeably to the several acts of the Legislature, down to the present time, shewing the situations of the Rivers, Bays, Harbours, Creeks, Rivulets, Islands and Shoals, within the same.

ALSO,

The Cities, Towns and Villages, Post-Offices, Post-Roads and Turnpikes, and all public or noted places, together with the most noted places in the adjoining States of New-York, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, contiguous to this State—in short, to contain every thing useful and interesting in such a work, comprised on a scale of four miles to the inch, and embellished with a handsome Engraving of the Arms of the State.

---

The Subscriber being induced to undertake the publication of a Map of New-Jersey, of the above description, from the incorrectness and inferior size of those heretofore published, has, after considerable labour and expense, so far accomplished his undertaking as to offer his prospectus to the Public.

The Maps of New-Jersey, which have heretofore appeared, (not to mention their manifest errors) have, from the smallness of the scale upon which they were laid down, been rendered incapable of detailing distinctly many of those interesting particulars which render such work especially useful and acceptable to the public. The Subscriber has, therefore, been induced to lay down his intended publication upon a scale sufficiently large to avoid this difficulty, and to enable him to give a distinct impression of the particulars above recited. As in this respect his Map will be superior to any heretofore published, so also, he flatters himself it will far excel in correctness any thing of the kind which has been offered to the public. He has exerted himself to combine in his intended publication, usefulness with elegance, and trusts he has so far succeeded as to be enabled, provided sufficient encouragement be given, to offer to his fellow-citizens a Map of the State of New-Jersey, superior in correctness, usefulness and beauty, to any which has ever before been published.

It not being the power of the Subscriber to exhibit the Map in all parts of the State, he has thought proper to submit it to the inspection of such gentlemen of information from different Counties as are present at the Seat of Government, and from the approbation of the work which these gentlemen have expressed, he is flattered with the expectation that his undertaking will meet with very general encouragement. A certificate of those who have examined the Map will hereafter be given to the Public.

WILLIAM WATSON,

Surveyor and Draughtsman.

Weymouth Township, Gloucester County,

N.J. November 5th, 1807.

CONDITIONS.

1st. As soon as a sufficient number of subscribers shall be received, the work will be put in the hands of an engraver and finished with all possible expedition.

2d. The Map will be handsomely engraved on copperplate, two feet and a half by three feet and a half, and struck off on paper of superior quality.

3d. the Map will be pasted and delivered to subscribers at the moderate price of Five Dollars each, to be paid on delivery.

4th. Any person subscribing, or procuring subscribers for ten copies, and becoming accountable for the money, shall be entitled to the eleventh gratis, or an equivalent in cash, and in the same proportion for a greater or less number. 1

The copyright registration for the map, contained in a volume in the clerk's office of the United States District Court in Trenton, New Jersey, is dated September 25, 1812:

A large & complete map of the state of New Jersey. The map to be divided into east & west & subdivided into counties & townships agreeably to the several acts of the legislature down to the present time. Shewing the situation of all the rivers, bays, harbours, creeks, rivulets, islands & shoals, within the same. Also, the tides, towns & villages, post-offices, post roads and turnpikes & all public or noted, together with the most noted places in the adjoining states of New York, Pennsylvania and Delaware, contiguous to this state—in short to contain every thing useful and interesting in such a work comprised on a scale of four miles to the inch, and embellished with a handsome engraving of the arms of the state. By William Watson, surveyor and draughtsman. 2

Despite Watson's hyperbole, his map lacks much of the topographical detail of William Faden's map, though it seems to adopt its coastal and river outlines. Arbitrary lines for roads and the boundaries of townships prove that he often drew from assumptions, not fact. For example, the far northern township of Harrington, shown squeezed between Pompton and Franklin Townships, was created in 1775, bounded by the Saddle and Hudson Rivers. Of course, the product was only as good as it sources. A month after publishing his prospectus, in another issue of the Trenton Federalist, Watson had solicited help from residents:

The subscriber engaged in the publication of a Map of the state of New-Jersey, being desirous to present to the public in as correct form as possible, conceives it necessary to solicit the assistance of gentlemen of information in different parts of the state, in procuring the drafts of roads, plots or surveys of townships, and any other information, in their neighbourhoods, that may tend to improve the work, confidently hoping that any person possessing such information and feeling an interest in having the parts in which he resides, laid down with precision, will freely communicate the same. William Watson, Weymouth Township, Gloucester County, New-Jersey. 3

Apparently, the help was not as forthcoming as he had hoped or expected.

In the winter of 1778, storms opened a waterway between Sandy Hook and the mainland, from the Atlantic to Spermaceti Cove. Watson shows the breach on his map. The opening added an interesting footnote to the Battle of Monmouth:

When the battle ended, the British started marching to Sandy Hook, a distance of fifteen miles. . . The baggage, coaches, horses, mistresses, and plunder of the rich British officers stretched out 12 miles behind them. . . At their campsites [in the Navesink Highlands], the British soldiers had to wait a week for their fleet to reach Sandy Hook Bay in order to carry them to New York. Also, they could not move until a pontoon bridge was built over the breach (called "the gut") carved out by the ocean the previous winter near the base of Sandy Hook, turning it into an island. Beginning July 5, about 12,000 British and Hessian troops marched across the inlet and boarded ships anchored in the bay. The colorful embarkation was watched by local citizens on surrounding hills. . . 4

On the map in Gloucester County, a large rectangular box bears the title "West Society or Weymouth Company Tract." This area was purchased in 1800 from the West Jersey Society of Burlington by a group of Philadelphia businessmen wanting to establish a forge and furnace complex to smelt the local bog iron. The following year they got permission from the state to dam the Great Egg Harbor River, and iron production began in 1802. The Weymouth furnace/forge supplied shot and other material to the U.S. government during the War of 1812. In the 1850s, its peak period of production, the tract also included a church, a gristmill, a sawmill, workers' homes, and wheelwright and blacksmith shops. Later, paper mills operated in the area through the rest of the century.

The reception of Watson's map was less than favorable. In October 1811, Governor Bloomfield had asked the state legislature to approve the purchase of twenty-five copies, to be exchanged for similar maps from other states. The members unanimously agreed. However, after the finished copies were supplied in October 1813—owing, according to Watson, to a lengthy illness in the engraver's family—a legislative committee examining the map issued a report claiming that it was "materially deficient":

That in such part as professes to lay down the situation of counties, towns, stream, and even state boundaries, it is wholly incorrect. The boundaries of many counties are erroneously laid down—the situation of townships misplaced, and noted ponds, streams, &c. placed at great distances from their real situation. The committee are therefore of opinion, that the said Map is not worthy of being transmitted to the other States... 5

Furthermore, they wanted Watson to repay the money he had received from the state. (The report was tabled for another reading.) Living at the time in Millville, New Jersey, Watson issued a lengthy rebuttal on the front page of The True American,6 essentially claiming that the legislature had plenty of time to examine the map before he had been paid, that he would gladly correct any errors they could specifically point out—how could they call in question other boundary lines when they did not know the boundaries of their own townships?—and that they had not given him the honor of appearing before the committee in person to address their complaints. The dispute died in the press.

Not much is known about the map's creator. On March 2, 1811, a patent for a stove was issued to a William Watson of Weymouth, New Jersey7. Certainly, invention and enterprise would be advantages in mapmaking. Colonial records mention a lieutenant in the Gloucester County militia named William Watson (1740–1817), who was promoted to captain, and served to the close of the Revolutionary War. His advanced age at the date of the map makes him suspect, however. The fact that the Weymouth Company Tract is a new and prominent thematic feature of the map suggests that its inclusion was more than incidental to Watson's local residence; possibly he worked there in some capacity and, hence, was promoting the business in his map.

◊ ◊ ◊

![1828: Thomas Gordon (1778–1848). "Map of the State of New Jersey: with Part of the Adjoining States" (Trenton, N.J.: Published by the author; Philadelphia: H. S. Tanner, 1828) [Historic Maps Collection, purchased with support from Henry Wendt, Class of 1955]. Wall map, with added color, 143 × 83 cm. Scale: 3 miles to 1 inch. (See back pocket for large facsimile.)](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fbackground%2F1828-gordon-state-map.jp2/full/!350,350/0/default.jpg)

A cornerstone map of New Jersey: the first "official" state map and the first large detailed map of the state. Alternating bands of color (pink, green, orange, yellow) separate adjacent counties; colored lines trace township boundaries. At this time, the state boasted fourteen counties: Bergen, Burlington, Cape May, Cumberland, Essex, Gloucester, Hunterdon, Middlesex, Monmouth, Morris, Salem, Somerset, Sussex, and Warren. With its large scale, the map locates all of the townships. The keyed symbols distinguish different church denominations and identify mills, furnaces, forges, taverns, and dwellings. The routes of the state's developing canal and turnpike systems are similarly displayed. The coastline consists completely of undeveloped marshes and beaches. Latitude and longitude marks (east from Washington, D.C.) form part of the map's border.

Recognizing the need years earlier (1799), the state legislature had established an exclusive corporation "for procuring an accurate Map of this State."8 Copies of the map would be distributed to township clerks and county courthouses. But nothing came of this venture.

!["Plan of a Company, for Procuring an Accurate Map of the State of New-Jersey" (Trenton: G. Craft, 1799) [courtesy of Joseph J. Felcone.] This is the only known copy of the broadside of the prospectus, with the signatures of fifteen Cape May County subscribers. Adjacent to the signatures of several subscribers is the notation "Money returned," with dates beginning in early January 1801. Copy of Aaron Leaming (1740–1829), prominent Cape May citizen.](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fbackground%2F1799-state-map-broadside.jp2/full/!320,320/0/default.jpg)

The plan was to sell two thousand shares at five dollars each to raise ten thousand dollars to fund the mapping activities. By the end of 1800, it was apparent that the money could not be raised for what was becoming a daunting project and would have to be returned.

Another attempt, however, in November 1822 proved extremely successful. "An Act to encourage the formation of an accurate Map of the state of New-Jersey"9 authorized a loan of one thousand dollars to Trenton surveyor Thomas Gordon "to enable him to procure additional surveys" and to cover additional mapping costs. This high-quality map was the result. The legislature bought 125 copies for state offices, colleges, and counties and, in 1831, ordered another 125, sending one to each township. Through revisions (see next map), this map held the standard for several decades.

The engraver of the map, H. S. Tanner (1786–1858), was also a respected cartographer. His 1829 large-scale map of the "United States of America" is considered one of the premier early American maps, and for its New Jersey section he credited Gordon's work:

This portion of my map [New Jersey], as well as the adjoining parts of New York and Pennsylvania, is from the able and scientific map of Thomas Gordon, which is projected and drawn on a scale of three miles to an inch, and is exceedingly minute and particular. This admirable map, which must have cost its author much time and money, was compiled partly from surveys made by Mr. Gordon, combined with others collected by him during the progress of his work, and published in 1828.

He then proceeded to argue the plight of the state mapmaker:

This, as well as every other good state map with which I am acquainted, has failed to reimburse the expenditure of its enterprising author; the spontaneous sales of the map, and the limited patronage bestowed on it by the Legislature of New Jersey, being, as I learn, entirely inadequate...State maps, or indeed local maps of any kind, whose sale must necessarily be limited, should be done by the public authorities.10

◊ ◊ ◊

![1833: Thomas Gordon (1778–1848). "A Map of the State of New Jersey with Part of the Adjoining States: Compiled under the Patronage of the Legislature of Said State" (Trenton, N.J.; Philadelphia, Pa.: Published by author, 1833) [Historic Maps Collection]. "Second edition, improved to 1833." Wall map, with added color, 160 × 83 cm. Scale: 3 miles to 1 inch.](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fintro%2F1833-state-map-gordon.jp2/full/!350,350/0/default.jpg)

A great number of changes are visible already, particularly in the growth of the state's spiderweb network of roads. In the key, a symbol for railroads has been added by necessity. The Camden and Amboy Railroad, shown for the first time, links Philadelphia and New York. Chartered in 1830 and completed in 1833, it was the state's first railroad. Dark lines identifying the Delaware and Raritan Canal and its feeder canal snake across the middle of the map. Begun in 1830, they were completed in 1834. Changes in some place names are under way: for example, Columbia is now "Hopewell or Columbia" in Hopewell Township (Mercer County); Slabtown is now "Slabtown or Jacksonville" in Springfield Township (Burlington County). Gordon would become the first librarian of the New Jersey Historical Society, founded in 1845.

◊ ◊ ◊

![1836: John T. Hammond. "Squire's Map of the State of New Jersey" (New York: B. S. Squire, Jr., 1836) [Historic Maps Collection]. Wall map, with added color, 68 × 49 cm. Scale: 10 miles to 1.5 inches. One of three known copies.](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fintro%2F1836-state-map-squires.jp2/full/!350,350/0/default.jpg)

This is another significant nineteenth-century wall map of the state, including eight insets of towns and cities around the border (clockwise from the right): Burlington, Jersey City, New Brunswick, Elizabethtown, Paterson, Rahway, Trenton, and Newark. The title vignette is an engraving of Paterson's Passaic Falls, which is providing power for the city's booming factories, mostly cotton and woolen mills; twenty-three are named and keyed on the city's inset map. (See the Passaic County section for a current view of the Passaic Falls.) Latitude and longitude degrees (west from Greenwich, England) are indicated in the pink part of the border, and distance between towns and junctures in the roads is given in miles, shown in numerals along their paths. The state appears divided in half—not east and west as in its colonial days, but north and south of the Philadelphia–New York commercial corridor, signified by the route of the Camden and Amboy Railroad. Roads and towns are concentrated in the northern half; by contrast, Monmouth County and the other "southern counties" are virtually undeveloped.

Bela S. Squire was a publisher who was active in New York City during the 1830s; Hammond drew and engraved most of his maps.

◊ ◊ ◊

![1860: Griffith Morgan Hopkins, Jr. "Topographical Map of the State of New Jersey: Together with the Vicinities of New York and Philadelphia, and with Most of the State of Delaware: From the State Geological Survey and the U.S. Coast Survey, and from Surveys" (Philadelphia: H. G. Bond, 1860) [courtesy of John Delaney]. Wall map, with added color, 172 ×142 cm. Scale: 2.5 miles to 1 inch.](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fintro%2F1860-state-map-kitchell.jp2/full/!350,350/0/default.jpg)

The largest map of New Jersey published in the nineteenth century: an attempt to show all the roads in the state. Despite its title, there is little topographical information in the map. Red lines border the twenty-one counties; townships are tinted in pink, yellow, blue, orange, or light green. (Note that all the townships in the state are named.) Inset around the sides are seventeen city/town maps—Belvidere, Beverly, Bordentown, Burlington, Camden, Elizabeth, Jersey City/Hoboken, Morristown, Mount Holly, New Brunswick, Newark, Newton, Orange, Paterson, Rahway, Salem, Trenton—and views of Camden, Delaware Water Gap, New Brunswick, Newark, Paterson, and Trenton. The presence of the branch of the Raritan and Delaware Bay Railroad through Monmouth County to Long Branch, which had just opened in June 1860, confirms the map's timeliness.

Also included on this huge cartographic tapestry are a state meteorological map by Lorin Blodget, broadly defining annual rainfall and average mean temperature regions, and a time dial, "showing the time at the several County Seats when it is 12 o'clock at the Capitol." (Though American and Canadian railroads began using time zones in 1883, standard time zones were not established by Congress until 1918; before that, most places relied on "solar time," or time determined by the sun's movement. That is what is clocked on this map's time chart.) Blodget (1823–1901) was an important figure in American climatology; his New Jersey climate map drew from his popular treatise Climatology of the United States (1857). The box at the left center of the map compares the "capacities of churches" by denomination: Methodists and Presbyterians account for more than half of the religious residents in New Jersey at this time.

A geological survey of New Jersey had begun in 1836–1840 under the direction of Henry D. Rogers, New Jersey's first state geologist. Unfunded for fourteen years, it was resurrected by William Kitchell (1827–1861), when he was appointed state geologist and superintendent of the newly formed New Jersey Geological Survey in 1854. (Kitchell had been secretary of the New Jersey Natural History Society.) However, after two short years, funding was again stopped until the New Jersey Agricultural Society pressured the legislature in 1860, lobbying for the Survey's potential agricultural and other benefits.

"An act relative to the geological survey of this state"11 was approved on March 15, 1860. The law allowed Kitchell the use of already-completed field maps, woodcuts, and survey apparatus—which he was obligated to return to the state after the completion of his work—but the resulting maps and reports from the new survey had to be published at his own cost. In addition, the law directed Kitchell to provide the state with ten copies of his new state map for the state library and state offices, to give one copy to the state agricultural society, and to deposit one in each county clerk's office for the benefit of the people. Under the direction of Kitchell, civil engineer Griffith Morgan Hopkins, Jr., compiled the latest work of the New Jersey Geological Survey and the U.S. Coast Survey. The result was this magnificent map, published privately in Philadelphia later that same year.

◊ ◊ ◊

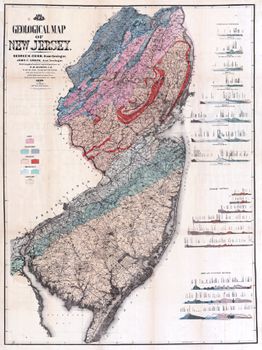

1868: Geological Survey of New Jersey. Geology of New Jersey (Newark: Daily Advertiser Office, 1868) [Historic Maps Collection]. A nine hundred-page report, with a large geological map in the back pocket, accompanied by a portfolio of eight additional geological maps on twelve sheets, titled "Geological Survey of New Jersey Maps." Several of the maps, in sections, have a scale of 2 miles to 1 inch.

After Kitchell's sudden death from pneumonia at the end of 1861, the office of state geologist lapsed for a few years. "An act to complete the Geological Survey of the State"12 passed on March 30, 1864. George Hammell Cook 1818–1889) was given the post and the charge. A former civil engineer and Rutgers professor, he had been Kitchell's assistant geologist during the survey years of the 1850s. In 1864, Cook also became vice president of Rutgers College; he had been instrumental in the institution's quest for land-grant status. (Rutgers's Cook College, today's School of Environmental and Biological Sciences, was named for him.)

Four years later, as required by the 1864 act, Cook produced these large-scale geological maps of the state to accompany his report. Hopkins was the cartographer. None of this work, however, filled the need for a thorough, accurate topographical map of the entire state.

◊ ◊ ◊

![1872: Title page of New Jersey's first state atlas. F. W. Beers. State Atlas of New Jersey: Based on State Geological Survey and from Additional Surveys by and under the Direction of F. W. Beers (New York: Beers, Comstock & Cline, 1872) [Historic Maps Collection].](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fbackground%2F1872-state-atlas-titlepage.jp2/full/!320,320/0/default.jpg)

First atlas of the state of New Jersey. (The first atlas of a U.S. state was Robert Mills's Atlas of the State of Carolina, published in 1825. David H. Burr issued his An Atlas of the State of New York in 1829. A state atlas of Delaware and a number of Pennsylvania and New York county atlases had appeared in the 1860s.) American surveyor Frederick W. Beers became one of the most prolific publishers of county atlases.

The geography was compiled from Cook's 1868 geological survey report, and the volume includes a smaller scale version of his geological map. Introductory sections on geology, climatology, and agriculture also borrow heavily from the earlier work of Cook and his associates. The atlas contains a complete list of New Jersey post offices, the 1870 state census (by county and township), the 1870 national census (by state and county), and a two-page United States map. The latter has an undivided Dakota territory and labels Oklahoma as "Indian Territory"; though a number of western states have not yet been admitted into the Union, they bear their proper names and borders. There are also maps for Philadelphia and New York City. As one would expect, there is a map for every New Jersey county, with borders circumscribed in dark red and townships differentiated in pink, yellow, light blue, orange, or green. On the sixty-one additional city, town, and village plans, public buildings and parks are identified, as are major commercial enterprises.

Sprinkled among the maps are public notices of businesses, presumably paid advertisements. Unlike county atlases, which often name and map private residences, these pages are the only places where personal names are mentioned in the atlas. The categories provide a sense of the various strengths of the business communities, and inventiveness, as always, stands out. In Mercer County, for example, among the attorneys, bakers, fruit canners, bankers, masons, and builders listed, one enterprising carpenter has monopolized the category of "Stair Builder." Interestingly, the only listed Mercer newspaper that still exists today is Princeton University's Princetonian, "devoted to local literature and college news."

The agrarian nature of the state is the dominant theme in the atlas:

New Jersey is an agricultural State. She has large manufacturing interests; her mining industry is valuable, and her means of communication by railroads, canals, and common roads are as extensive as in any portion of our country; still, agriculture is her largest interest [p. 22].

Cook goes on to point out that half of the country's crop of cranberries is raised in New Jersey. Large tracts of wet pastures and swamps have been drained to make dry, tillable fields; the reclaiming of tide-marshes in Salem and around Newark and Elizabeth has converted "unsightly wastes" into productive meadows. And he claims that abundant green marl, a marine deposit, makes a remarkable natural fertilizer.

◊ ◊ ◊

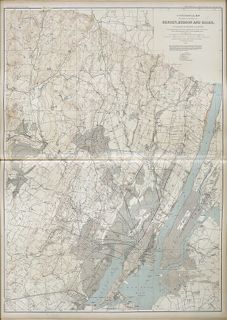

![1884-1888: Title page of New Jersey's first topographical atlas. Geological Survey of New Jersey.Atlas of New Jersey (New York: Julius Bien & Co., [1888]) [Historic Maps Collection]. Atlas of lithograph maps. Seventeen sheets of overlapping regions, dated 1884 to 1887; one state map, dated 1888. (Later copies added a state relief map and a state geological map.)](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fbackground%2F1888-state-atlas-titlepage.jp2/full/!320,320/0/default.jpg)

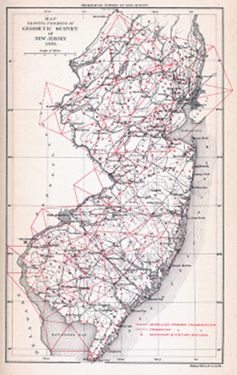

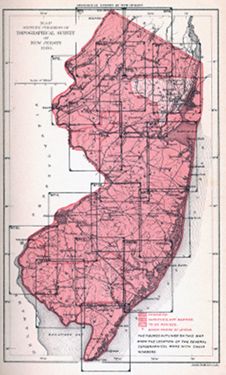

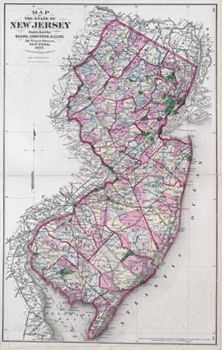

!["The State of New Jersey: From Original Surveys Based on the Triangulation of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey" ([Trenton, N.J.]: Geological Survey of New Jersey, 1888). Large lithograph map, 88 × 62 cm. A general reference map, showing roads and civil divisions. Scale: 5 miles to 1 inch.](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fintro%2F1888-state-map-from-atlas.jp2/full/!750,750/0/default.jpg)

The first published topographical survey of a U.S. state.

At the beginning of the Survey no such work as is here given entered into our plans. But as the successive reports appeared, and as the attempts at descriptive geology were made, it became apparent that for the study and preparation of useful geological reports it was necessary to have accurate maps—maps which would show the locations of all the important geographical points, and also the outlines and elevations of the hills and valleys, and their heights above the sea level. There were no such maps of New Jersey in existence, nor, indeed, of any others of the United States.13

The topographical surveys depended on having precisely located points (latitude/longitude/elevation) around the state, resulting in a network of geographic triangles. The geodetic work to fix these points, about which the survey maps could be arranged and located, was directed by the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, with the cost borne by the federal government; the actual field surveying was conducted by the Geological Survey of New Jersey. The triangulation work began at Mount Rose (Mercer County) in 1875, and proceeded northward. In 1883, the surveying of the southern part of the state started. By then, the U.S. government had assumed the cost of concluding the project, with both Surveys working closely together and sharing the benefits.

![1869: "Plane Table." From The Plane - Table and Its Use in Topographical Surveying. From the Papers of the United States Coast Survey (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1869) [General Collection]. Instrument commonly used in the field for this topographical surveying work.](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fbackground%2F1869-plane-table001.jp2/full/!320,320/0/default.jpg)

![1875: "Outline Map Showing the Triangulations Made by the U.S. Coast Survey: Including the Primary Stations Selected in 1875." From Annual Report of the State Geologist, for the Year 1875 (Trenton, N.J.: [The Survey], 1875) [Historic Maps Collection].Large lithograph map, 76.6 × 46.4 cm.](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fbackground%2F1875-state-map-triangulations.jp2/full/!750,750/0/default.jpg)

Erecting scaffolds and utilizing tripods and theodolites, the surveyors proceeded around the state, through thickly wooded areas, over hills and ridges, often utilizing the spires of churches and public buildings as reference points. Examples include the Cape May lighthouse, Flemington's Methodist Church spire, Princeton College's cupola—presumably that of Nassau Hall—and the statehouse dome in Trenton. At its completion, the survey had established 457 such points, with a precision measured by inches. The person who had been responsible for all of the topographical surveys since 1879 (and who wrote most of Cook's final report) was the Rutgers graduate and civil engineer C. C. Vermeule (1858–1950).

The seventeen regional maps and the state map of this atlas represent the culmination of more than two hundred years of cartographic effort. "At long last, accurate maps of the state could be prepared with confidence."14