Nova Cæsarea: A Cartographic Record of the Garden State, 1666-1888

Historical Background Maps

State Maps

As one might expect, early New Jersey state maps were attempts to formalize, consolidate, and promote territory. In the process, this Mid-Atlantic province/state gained greater attention from land speculators and immigrants.

![1777: William Faden (1749–1836). "The Province of New Jersey, Divided into East and West, Commonly Called the Jerseys" ([London]: Wm. Faden, Charing Cross, December 1st, 1777) [Historic Maps Collection, purchased by the Friends of the Princeton University Library]. Copperplate map, with added color, 78 × 57 cm. Scale: "about 69½ British miles to a degree" (roughly, 6.6 miles to 1 inch).](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fbackground%2F1777-faden-state-map.jp2/full/!350,350/0/default.jpg)

The most popular early map of New Jersey, which settled the boundary between New Jersey and New York. A fertile farm scene with a strange-looking raccoon frames the title. As the note below the vignette states, the map is based on the survey work of Bernard Ratzer, a British army officer who had been appointed in 1769 by King George III's boundary commissioners to help settle the century-old dispute. The northwest point of the state is given as the meeting point of the Delaware and "Mahacamack" (today's Neversink) rivers. From there to the west side of the Hudson River, angling down to a latitude of 41º, the boundary line runs in a southeasterly direction.

In 1882, the boundary line was re-examined, and the old stone markers that had been set in 1774—most of which could still be found—were replaced with new granite milestones.

Two other lines are prominently displayed on the 1777 map: "Division Line Run in 1743 between East New Jersey and West New Jersey" and "Keiths Line in 1687." George Keith (1639? –1716), surveyor general of East Jersey, was hired to survey the division line between the two provinces in 1687. Why he stopped at the South Branch of the Raritan River (near today's Three Bridges) is not clear. The rest of the boundary was later continued along the North Branch, the Passaic River, and the Pequannock Rivers to New York State as a basis for county boundaries.

Though the provinces united in 1702 to form the royal province of New Jersey, another, later version of the division line—also known as the Quintipartite Deed line after the five partners that had acquired Lord Berkeley's share in 1676—was surveyed by John Lawrence (1709–1794) in 1743, primarily to clarify private property rights. On maps, it was usually called the Lawrence Line.1 It is still used today to resolve land titles.

In this colonial era map, New Jersey consists of twelve counties: Bergen, Burlington, Cape May, Cumberland, Essex, Gloucester, Hunterdon, Middlesex, Monmouth, Salem, Somerset, and Sussex. There is an extreme scarcity of roads in the southern part of the state, and they are virtually nonexistent along the coast. It is interesting that the English map's sole historical note acknowledges where the Swedish first established a settlement (Helsingburg, below Salem on the Delaware River), but there are no similar references to the Dutch. Small black rectangles mark the general locations of buildings, either private or public, but the only one named is Nassau Hall of the College of New Jersey in Princeton.

William Faden, the map's maker, succeeded in the London business of Thomas Jefferys after he died in 1771. His prolific, fine engravings made him one of the great cartographers of his era. This map of New Jersey was included in his 1777 landmark publication The North American Atlas: Selected from the Most Authentic Maps, Charts, Plans, &c., Hitherto Published. At its time, the map was the largest of the province that had been published. Despite obvious errors in the depiction of roads and county boundaries, it remained the standard for decades.

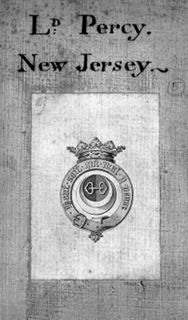

Princeton's copy of the map bears a unique provenance: it belonged to Hugh Percy, second Duke of Northumberland (1742–1817), and bears his family bookplate on the verso.

As a member of Parliament, Percy had voted against the repeal of the Stamp Act in 1766, but gradually grew opposed to the king's policies regarding the American colonies. As a British officer, however, he dutifully agreed to go to America to lead his brigade. He participated in the Battle of Lexington and Concord and the Battle of Long Island in the American Revolution.

... [A]t Lexington and Concord on 19 April 1775 Percy played a crucial role in saving Lieutenant-Colonel Smith's force from destruction as it retreated to Boston. Percy's brigade, together with two field pieces, met Smith's beleaguered column on the road between Menotomy and Lexington. Percy's troops held the enraged Massachusetts militiamen at bay while Smith's men regrouped, and then escorted Smith's battered command back to Boston under heavy fire. His coolness was widely praised, and he became the hero of the hour in besieged Boston. In July 1775 he was appointed major-general in America, and in September major-general in the army.2

Still disenchanted with the war and resenting what he considered condescending treatment by General Sir William Howe, the British commander-in-chief, he returned to England in 1777, the year of the map. In this cased format (dissected into sections and mounted on linen for folding into a case), one might assume that Percy used the map for reference in subsequent years.

◊ ◊ ◊

![1784: "The State of New Jersey." Copperplate map, 57.3 × 26.7 cm. From The Petitions and Memorials of the Proprietors of West and East-Jersey, to the Legislature of New-Jersey: Together with a Map of the State of New-Jersey, and the Country Adjacent: and Also an Appendix . . . (New York: Shepard Kollock, [1784]) [Rare Books Division]. Scale: 40 miles ("69½ statute miles") to 1 degree.](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fbackground%2F1784-state-map.jp2/full/!350,350/0/default.jpg)

First map of New Jersey to be printed in America. The map contains three lines dividing East and West Jersey. Further east of the Keith Line and the Quintipartite/Lawrence Line is the new "Ideal Line to Mahacamack claimed by West Jersey Proprietors since the Year 1775." The map is based on (extracted from) Ratzer's map mentioned above.

Though all three division lines begin in Little Egg Harbor, halfway down the Jersey coast, they take different paths northward. Of concern to the petitioners is the pie-slice-shaped tract of land, estimated at four hundred thousand acres, created between the angle of the Quintipartite Line that runs to latitude 41º40′3 and their "ideal" line, which ends at the junction of the Delaware and Mahacamack (Neversink) Rivers. Because that point had become the official northern border of New Jersey with New York and Pennsylvania, the proprietors of West Jersey felt that their line should become the true boundary between West and East Jersey for private property rights issues. The problem lay in its retrospective application: property owners had been using the Quintipartite/Lawrence Line for more than forty years. As a result, the New Jersey Legislature was not convinced by these petitions to make any changes.

Compiled by John Rutherfurd (1760–1840), a land surveyor and politician, the pamphlet was one of several that were occasioned by land disputes between the East and West Jersey Proprietors. (Rutherford, New Jersey, is named for his family, which owned much of the land in that area.) Princeton's copy of the volume bears his owner's signature.