Nova Cæsarea: A Cartographic Record of the Garden State, 1666-1888

New Jersey Coast: First Atlas (1878)

![Title page. T. F. Rose. Historical and Biographical Atlas of the New Jersey Coast (Philadelphia: Woolman & Rose, 1878) [Historic Maps Collection]. 390 pp., including illustrations and maps.](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fcoast%2F1878-title-page.jp2/full/!750,750/0/default.jpg)

Title page. T. F. Rose. Historical and Biographical Atlas of the New Jersey Coast (Philadelphia: Woolman & Rose, 1878) [Historic Maps Collection]. 390 pp., including illustrations and maps.

First atlas of the New Jersey coastal regions. Displayed in these pages is the golden age of the Jersey shore, certainly the state's most volatile landscape to be mapped over the past 350 years. From the north point of Sandy Hook to the south point of Cape May, the coastline stretches for about 130 miles, embracing parts of Monmouth, Ocean, Burlington, Atlantic, and Cape May Counties. The volume's numerous elaborate engravings of public and private properties and the detailed hand-colored plans of towns and villages—all demonstrate the publisher's desire "to preserve and perpetuate in some substantial form a record of the past and present condition of that portion of New Jersey . . ." [preface].

The first hundred pages document the history of the New Jersey coast, by county and township, and provide biographical sketches of the "most prominent citizens along the coast, who, by their talents, industry, or means, had materially aided to advance [its] growth and prosperity" [p. 18]. Portraits of some of them are included. In addition, there is an alphabetical list of more than two hundred known shipwrecks, followed by a north-south listing of another 125 vessels wrecked between Manasquan and Barnegat Inlets. By the 1870s, a string of lighthouses had been erected and/or refitted "so that in sailing the light of one is not lost till the next is in sight." Also, a system of forty-one lifesaving stations had been organized, accelerated by funding from Congress in 1871. Their locations are plotted on the coastal maps.

Large storms have ravaged the Jersey coast time and again. The headline of a nineteenth-century New York Tribune article proclaimed "A Coast Line Changed":

![Cover. T. F. Rose. Historical and Biographical Atlas of the New Jersey Coast (Philadelphia: Woolman & Rose, 1878) [Historic Maps Collection]. 390 pp., including illustrations and maps.](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fcoast%2F1878-coast-atlas-cover-title.jp2/full/!350,350/0/default.jpg)

Cover. T. F. Rose. Historical and Biographical Atlas of the New Jersey Coast (Philadelphia: Woolman & Rose, 1878) [Historic Maps Collection]. 390 pp., including illustrations and maps.

The storm is raging with great violence along the entire New-Jersey coast from Sandy Hook Point to Cape May City, and up the Delaware River as far north as Trenton. It is beyond question the most severe storm that has visited that portion of the Atlantic coast within the memory of the present generation. It is impossible to estimate in dollars and cents what the loss will be. . . . The contour of the coast has been changed to a remarkable degree in many places [September 12, 1889].

Those words equally might have described the destruction wrought by Hurricane Sandy in October 2012. Since so many of the oceanfront structures pictured in this volume no longer exist, its pages raise a particularly poignant voice for the Victorian life that was lived "down the shore" in its businesses, residences, resorts, and entertainments.

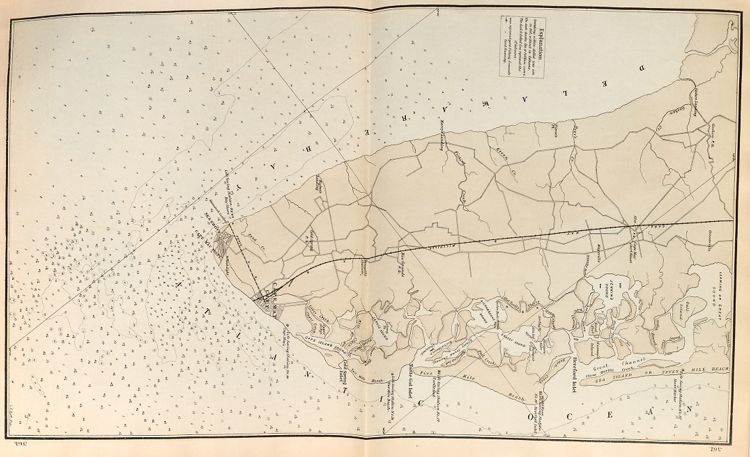

The coastal maps, obtained for the atlas by special permission from the United States Coast Survey, constituted, at the time, the most complete delineation of the New Jersey coast ever published.

◊ ◊ ◊

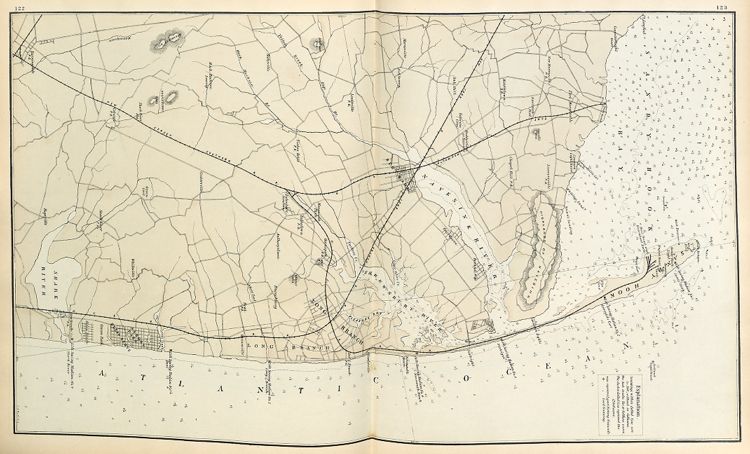

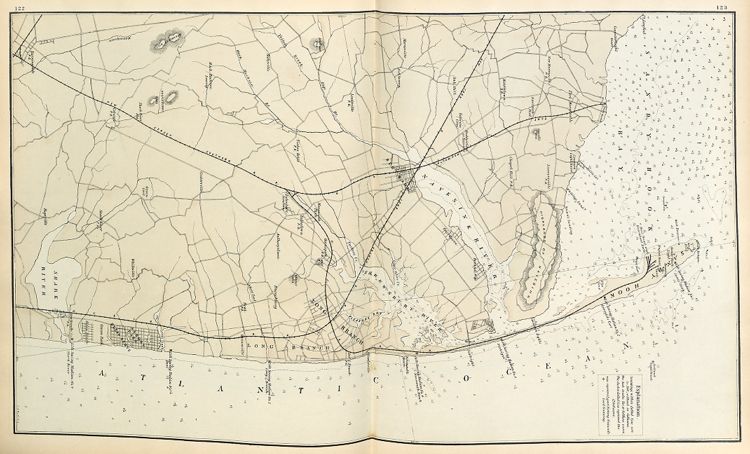

"Coast Section, no. 1," from Sandy Hook to Ocean Beach. Lithograph map, with added color, 53.8 × 30.6 cm. Includes Life-Saving Stations Nos. 1–7: Sandy Hook, Spermlets Cove, Seabright, Monmouth Beach, Long Beach, Deal, Shark River.

2013: Sandy Hook Lighthouse. Built in 1764, this is the oldest continuously operating lighthouse in the nation. Originally, the tower stood just five hundred feet from the tip of Sandy Hook. Today, owing to the growth of the point caused by longshore drift, the lighthouse is 1.5 miles inland from there. The adjacent lighthouse keeper's dwelling dates from 1883.

2013: Life-Saving Station No. 4 (Monmouth Beach). This was the second one to be established on the Jersey coast. The present site was acquired in 1894.

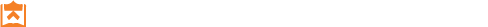

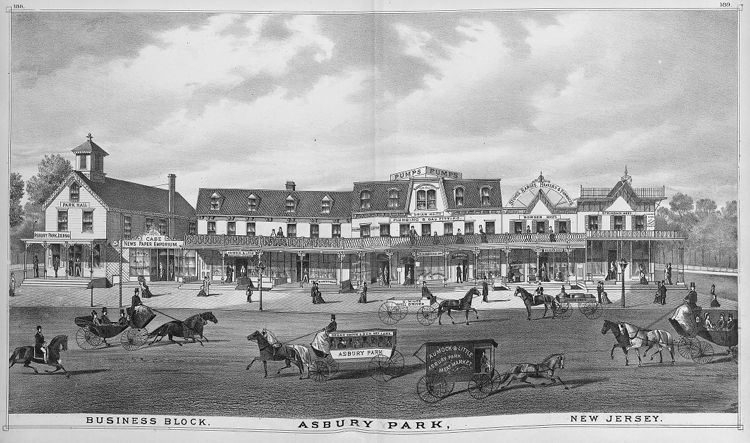

"Asbury Park Business Block" (1878)

2013: View of Ocean Grove bathing houses and pier today

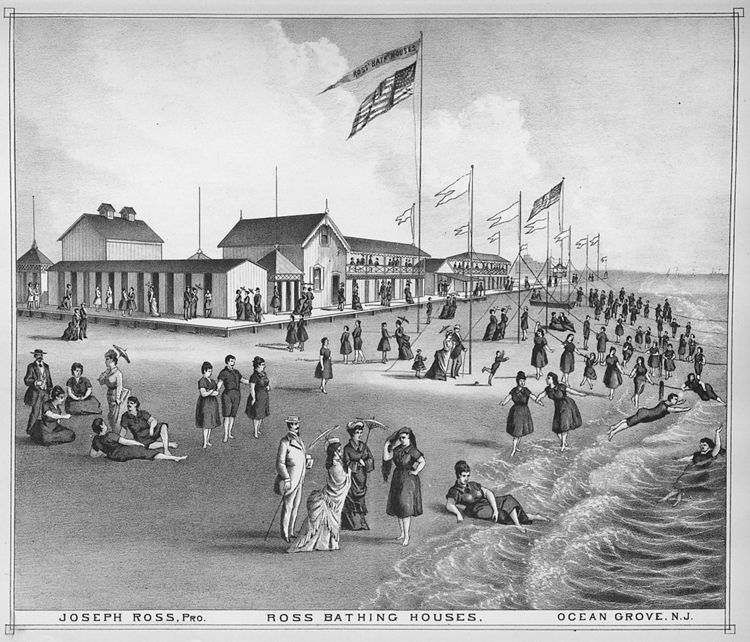

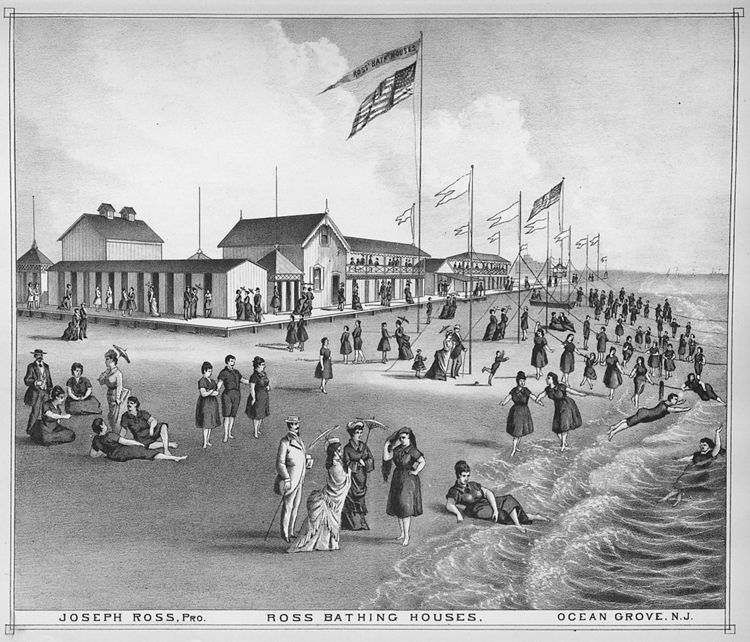

"Ross Bathing Houses" (1878). Flags were flown during hours suitable for "bathing," but were removed during Ocean Grove's camp meeting services. No bathing was permitted on Sundays. Note the lifelines that provided novice or timid swimmers a sense of security as they ventured out into the waves. Ross's two-story pavilion had a seating capacity for about eighteen hundred people.

◊ ◊ ◊

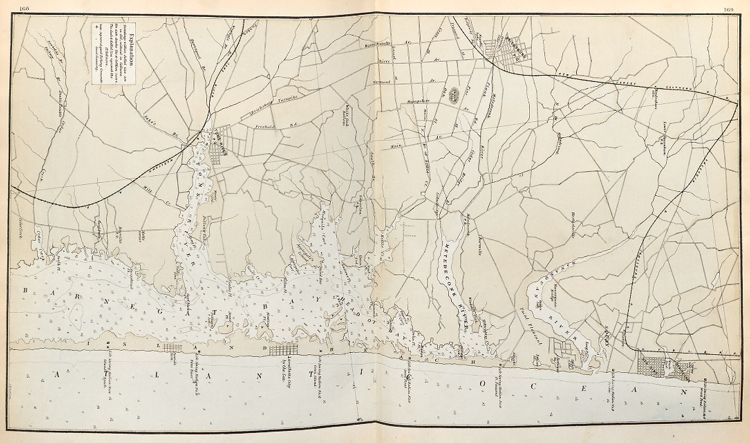

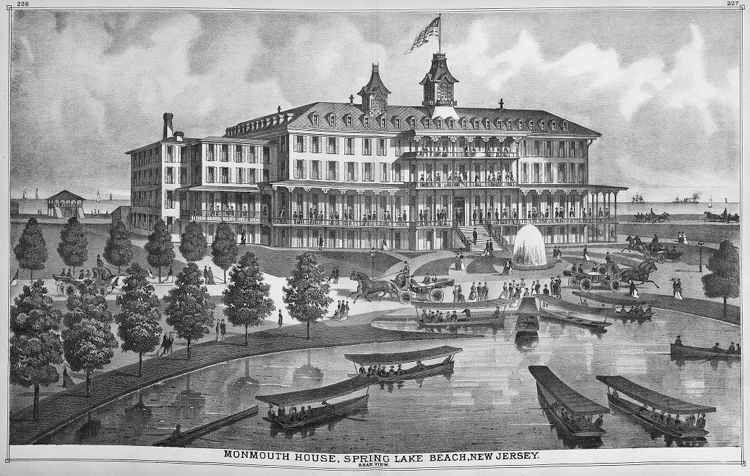

"Coast Section, no. 2," from Spring Lake to Island Beach. Lithograph map, with added color, 52.3 × 29.4 cm. Includes Life-Saving Stations Nos. 8–14: Wreck Pond, Squan, Point Pleasant, Swan Point, Green Island, Toms River, Island Beach.

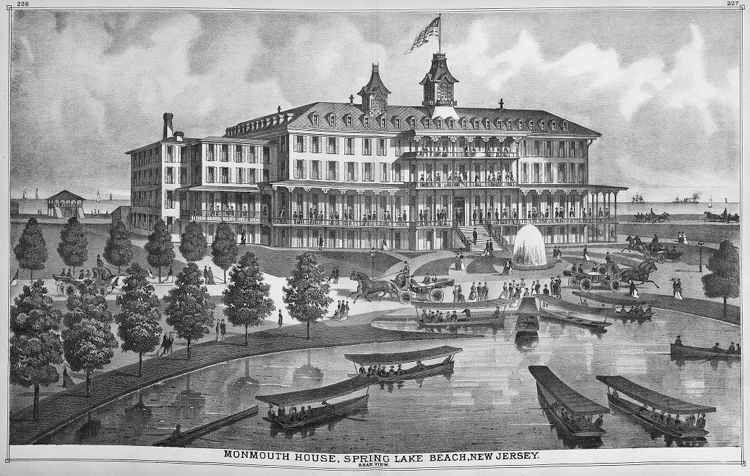

2013: View of the end of the lake today. The Essex and Sussex Hotel, built in 1914, is now a condominium complex essentially occupying the former Monmouth House site.

1878: Monmouth House. Spring Lake was a farming and fishing community until railroad men and affluent Philadelphians formed the Spring Lake Beach Improvement Company in March 1875. Their development plan, drawn up by Philadelphia engineer Frederick Anspach, included a grid of streets and lots, with a large hotel at the end of the lake facing the ocean as its focal point. A palatial structure with 250 rooms and broad piazzas, and "electric calls" in every room, the hotel was completed in 1876 but succumbed to fire on September 19, 1900.

◊ ◊ ◊

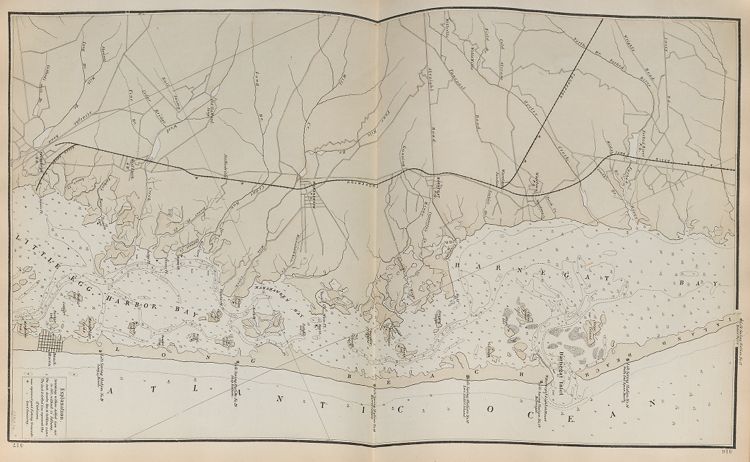

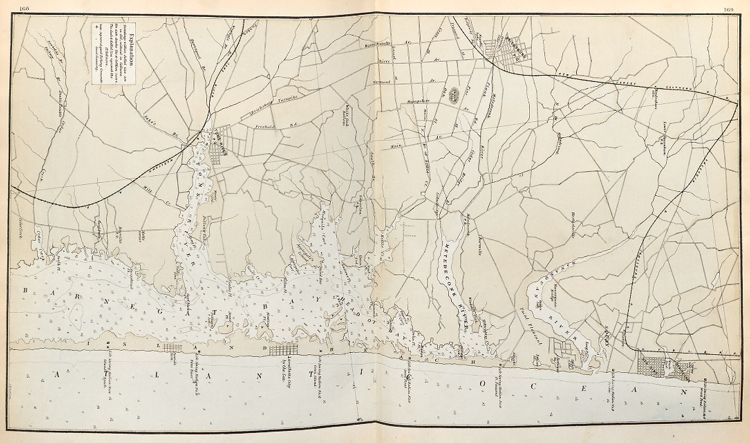

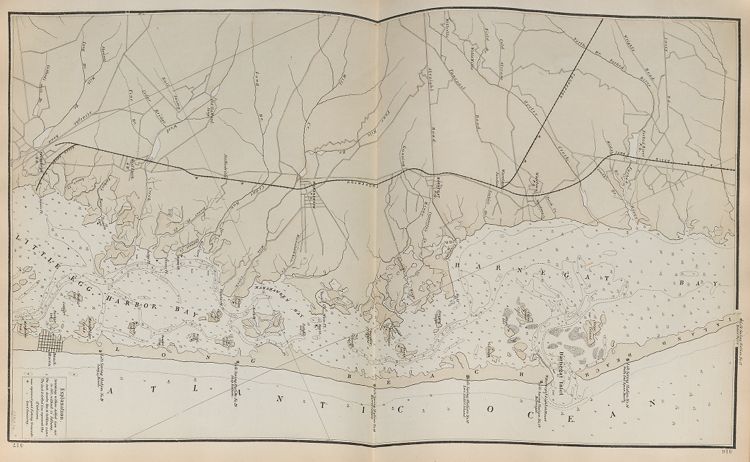

"Coast Section, no. 3," from Island Beach to Beach Haven. Lithograph map, with added color, 52.7 × 30.3 cm. Includes Life-Saving Stations Nos. 15–21: Forked River, South End Squan Beach, Barnegat, Love Ladies Island, Harvey Cedars, Ship Bottom, Long Beach.

◊ ◊ ◊

2014: View looking far south towards Brigantine and Atlantic City, from the parking lot at the end of South Long Beach Avenue in Holgate. of the state’s 130-mile shoreline, over thirty miles are completely undeveloped. shown here is part of the Holgate unit of the Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge, which is a section of a 10.8-mile gap in development consisting of Holgate, Little Beach Island, and the northern part of Brigantine Island.

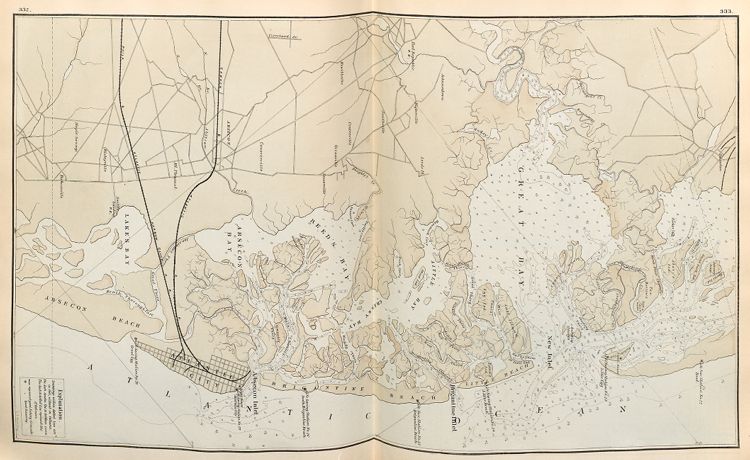

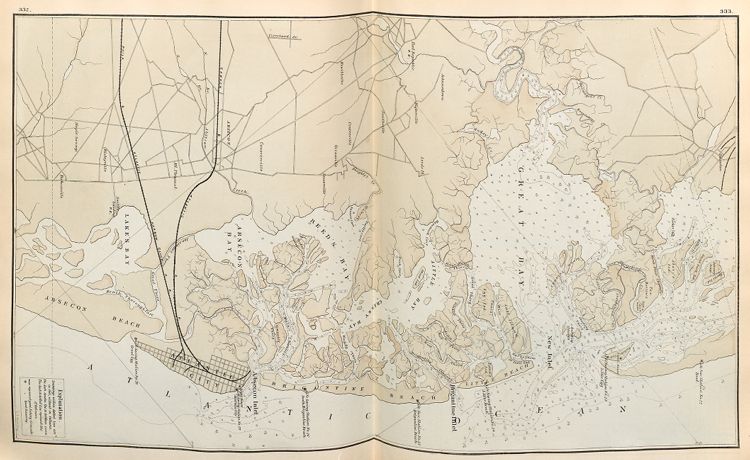

"Coast Section, no. 4," from New Inlet to Absecon Beach. Lithograph map, with added color, 51.7 × 29.7 cm. Includes Life-Saving Stations Nos. 22–28: Bond, Little Egg, Little Beach, Brigantine Beach, South Brigantine Beach, Atlantic City, Great Egg.

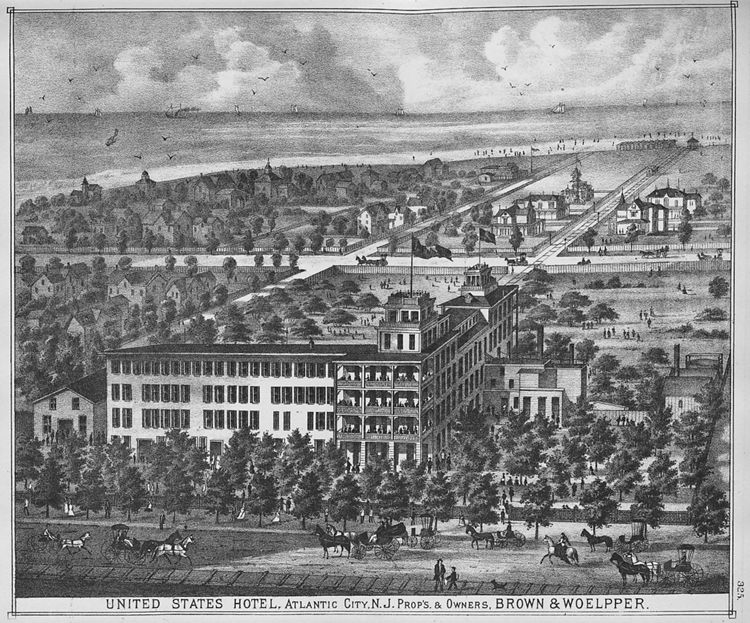

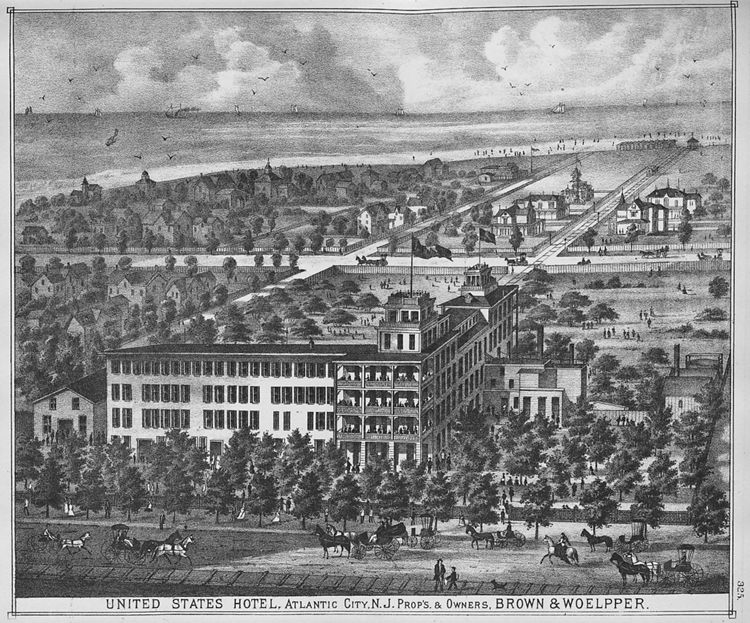

In the 1870s, half a million people were arriving in Atlantic City by train every year. One has to imagine that many of them ended up staying at the United States Hotel. To great fanfare, Atlantic City formally opened on Wednesday, June 16, 1880: America's playground was born. Today, the city is challenging Las Vegas as America's gambling mecca.

2013: Currently, the whole block is a parking lot for the Showboat Atlantic City Hotel and Casino.

"United States Hotel" (Atlantic City, 1878). Owned by the Camden and Atlantic Railroad, this hotel was the resort's first public lodging and the country's largest, with more than six hundred rooms and grounds covering fourteen acres, bordered by the Atlantic, Pacific, Delaware, and Maryland Avenues. In the early 1890s, visitors from New York City would receive railroad fare, lunch en route, and three days' accommodation at the hotel for $12.50. But development in the city surged ahead, and by 1900 the hotel was completely demolished to make room for other projects.

◊ ◊ ◊

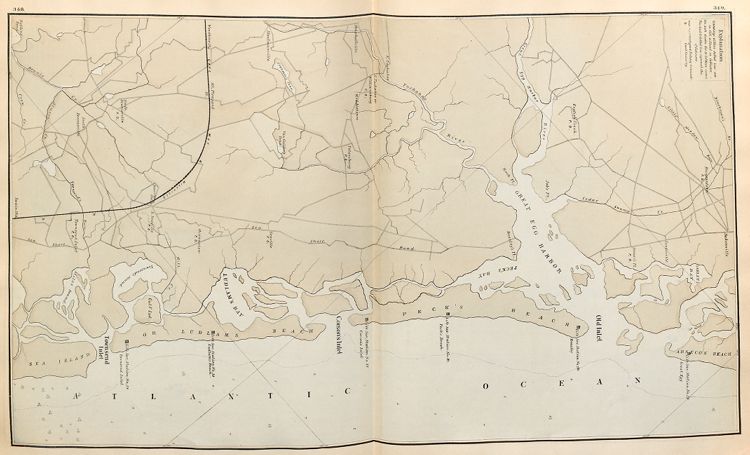

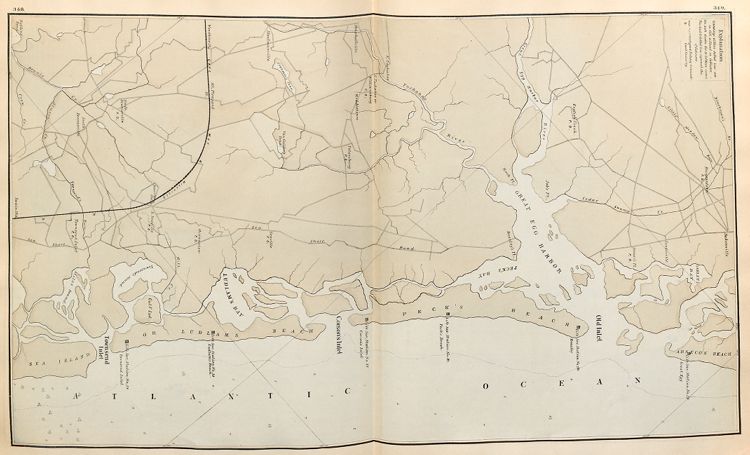

"Coast Section, no. 5," from Absecon Beach to Sea Island. Lithograph map, with added color, 51.6 × 29.8 cm. Includes Life-Saving Stations Nos. 29–34: Great Egg, Beazley, Peck's Beach, Corson's Inlet, Ludlam's Beach, Townsend Inlet.

◊ ◊ ◊

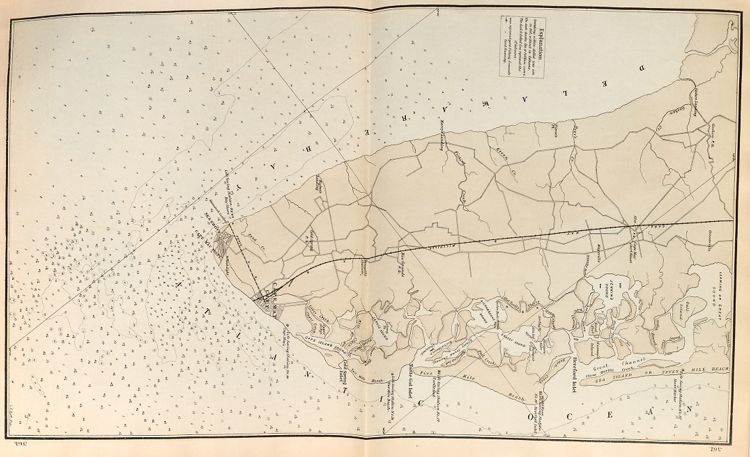

"Coast Section, no. 6," from Hereford Inlet to Cape May. Lithograph map, with added color, 52.3 × 30 cm. Includes Life-Saving Stations Nos. 35–40: Stone Harbor, Hereford Inlet, Turtle Gut, Two Mile Beach, Cape May, Bay Shore. (The table on p. 57 identifies two Cape May stations as Nos. 39 and 40, and Bay Shore as No. 41. However, only one Cape May station, No. 39, is shown on the map, and No. 40 is Bay Shore.)

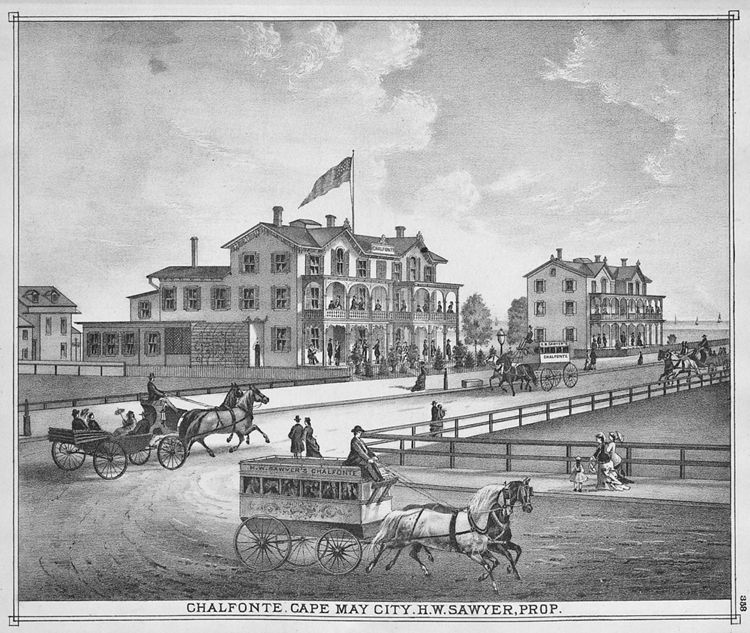

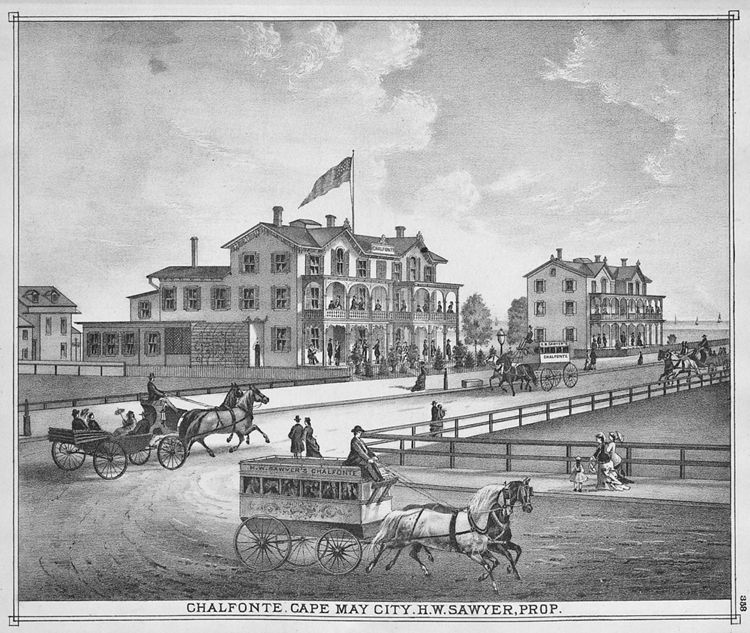

2013: The Chalfonte today. This is the oldest continuously operating hotel in Cape May.

Chalfonte. Cape May City (1878). Two years prior to this 1878 image, the site was a salt marsh. The energetic proprietor, Henry Washington Sawyer, had previously operated the Ocean House. Sawyer was an officer in the 1st Regiment, Cavalry, New Jersey Volunteers, and his Civil War record reads like a dramatic novel. In Woodstock, Virginia, his horse was shot out from under him and landed on his right leg, resulting in a permanent, painful limp. On a reconnaissance mission, he was shot in the stomach. He received two serious wounds in his thigh and cheek at the Battle of Brandy Station, before his horse was killed, throwing him out of the saddle and knocking him senseless. Captured by Confederates, he ended up in Richmond's infamous Libby Prison. Sawyer's name was one of two drawn from a pool of seventy-five captains in a lottery to determine who would be executed in retaliation for previous Union executions of two Confederate officers. His wife's personal plea with President Abraham Lincoln ultimately won him a stay of execution and then an exchange for two Confederate prisoners, including the son of Robert E. Lee. Sawyer returned to his command and served out the rest of the war with distinction. He retired to his home in Cape May, where he began a successful career in hostelry. He also served as superintendent of the U.S. Life-Saving Service for the New Jersey coast. Sawyer died in Cape May in 1893 and is buried in the Cold Spring Presbyterian Cemetery there.

Back to Top

![Title page. T. F. Rose. Historical and Biographical Atlas of the New Jersey Coast (Philadelphia: Woolman & Rose, 1878) [Historic Maps Collection]. 390 pp., including illustrations and maps.](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fcoast%2F1878-title-page.jp2/full/!750,750/0/default.jpg)

![Cover. T. F. Rose. Historical and Biographical Atlas of the New Jersey Coast (Philadelphia: Woolman & Rose, 1878) [Historic Maps Collection]. 390 pp., including illustrations and maps.](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fcoast%2F1878-coast-atlas-cover-title.jp2/full/!350,350/0/default.jpg)